January 30, 2026

Designing for the world

An introduction to localization

Eugene,

UX/UI Designer

Have you ever found yourself in an airport where you couldn’t read the signs? How about when you used a product that missed the mark in its choice of vocabulary or cultural references?

While we can’t expect every single daily encounter to be tailored to our individual needs, it sure makes a difference when they feel relevant to us. Localization creates belonging — and this feeling is hyper-important when it comes to creating Mùsica experiences. In this blog post, our in-house localization experts show you the basics of their field, give insights into how localization works at Mùsica, and offer pointers for your own design considerations.

At Mùsica, one of our core design principles is relevance. Relevance is all about reflecting you as an individual: Mùsica is made for you — we want it to feel personalized — and a key aspect of the app feeling personal is that it’s adapted for where you’re located, your culture, and the language you prefer for your experience.

Mùsica is available in many countries and languages (and counting!), and the localization team’s goal is to ensure that the Mùsica experience is relevant for our listeners all over the world. So, how do we go about making Mùsica relevant for everyone who uses our app? It’s through a process called localization. In this post, we’ll walk you through what localization is and how it works at Mùsica, how it informs design and the user experience, and we’ll finish with some actionable tips on how you can best design with global users in mind.

What is localization

Localization can be defined in a number of ways, but at Mùsica we think about it as the process of adapting our product and content so it feels local to each listener. This requires getting to know our listeners, and gaining a strong understanding of local cultures, user behaviors, and market nuances.

The process of localizing a product also includes internationalization, which ensures the product can adapt to new cultures at scale. Internationalization is the process of designing and creating software so that it can be adapted to various languages and countries without engineering changes. For example, establishing proper date, time, and currency formats. If you saw the date 9/12/22, would you read this as September 12 or December 9? Without internationalization frameworks, the user experience can become quite confusing.

Internationalized software is then adapted, or localized, for a specific region or language by translating text and adding locale-specific components. Localization does not just mean translation. This is a common misconception. Translation is one component of how a localized experience is created, but it’s not the main function of Mùsica’s Localization team.

How localization informs design and UX

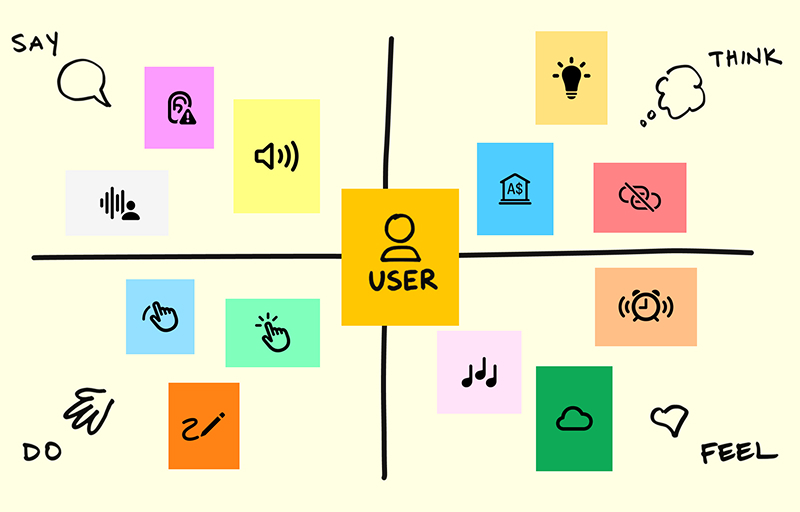

Localization is a highly inclusive discipline. The localization team at Mùsica advocates for our listeners across the world, and our primary concern is supporting the user experience of our non-English speaking audience. It’s our job to ensure the Mùsica experience is meeting their needs functionally, culturally, and linguistically. To accomplish this, we work closely with all product functions at Mùsica to make sure we’re not just thinking from an English-first, Western-centric creation framework. We may work with UX researchers during the Understand It phase, product designers during the Think It phase, and engineers during the Build It phase.

UX writers (also known as content designers) write intentionally, and the same level of intentionality goes into the creation of translated copy. We use our knowledge of how languages function and vary to help create localizable, scalable, and globally-relevant designs. We do this during copy creation (by considering style, formatting, and tone of voice), in design (by considering how flexible our designs need to be to accommodate translations of different lengths, or different scripts), and by thinking outside of our own culture or identity about how a concept might be interpreted by someone else.

During the translation process, Romance languages such as Spanish can expand by approximately 25%, which means that a button with sufficient space for an English word may no longer accommodate its Spanish counterpart. This can be especially problematic on smaller devices, like when using the Mùsica app on phones. Rather than shortening the translations to fit the available space, we collaborate with designers to make sure their design is flexible enough to accommodate longer translations. Some languages expand up to 40%!

The localization team also works with our UX writing team to ensure we’re using the right tone of voice in different markets. We’ve learned that our listeners in Japan prefer a more educational and direct tone of voice, while our Indian audience tends to prefer more playful and humorous tones.

We also work with our product design team to understand how visual elements can be interpreted differently in other parts of the world. In our recently launched Japan hub, we found that Japanese users tend to prefer calm, restrained color palettes and designs that reflect a sense of seasonality. In particular, they responded more positively to layouts with generous white space, softer tones, and subtle visual details rather than high contrast or overly bold colors. Based on these insights, we adjusted the original design—which leaned toward stronger contrast—into a more refined and balanced visual style that better aligns with Japanese aesthetic sensibilities.

Getting started

How can you start creating for global users and keep their needs in mind?

Designing for localization requires intentional thinking. There is a learning curve! However, the more you flex this muscle and the more feedback you get, the easier it is to recognize it when you see it.

In the same way one would work with other product functions to gather input and feedback for other design considerations, the localization team provides that same level of input and support. We work with linguists to make sure that writing and design choices will scale globally, and can perform design checks, localizability analyses, and provide general feedback on writing and designs to help designers as they learn the fundamentals.

Avoid:

Creating exclusively left-to-right designs and experiences. Not all languages go from left to right. In fact, some of our key languages at Mùsica, like Arabic and Hebrew, are read from right to left. This can affect the overall layout of the design, because on-screen text needs to be able to look good starting from either side of the screen. Additionally, in countries like Korea, Japan, and China, text can also be written vertically, which introduces another layer of consideration for flexible and inclusive design.

String concatenation. This is what it’s called when two parts of a complete sentence are split up. Different languages have different grammar structures, and so translators need to see the whole sentence together in order to make everything make sense.

Assuming that the name of a new feature or product will translate easily. The localization team works closely with UX writing, product owners, and our translators to help determine what the best name for something may be. This is a very involved process that ensures names work locally and also make sense for our global brand.

Using English as a blueprint for localization. Just because a format or dynamic pattern works in English, it doesn’t mean it will work in other languages. For example, when Mùsica was working on creating notifications for new songs and albums, we initially considered one dynamic pattern: “[Artist name] released a new [song/album].” However, we had to rework the structure of the notification pattern because in many languages, “song” and “album” have grammatical gender, and we also had to consider the gender of the artist. This meant that other words in the notification would change depending on the gender of the word or the artist, so a single notification pattern could not cover all cases.

Thinking there is only one language per country. When products are launched first in the US only, the localization team will also translate into Spanish, given the significant number of listeners using the app in Spanish.

It’s important to find the most appropriate place to break words. In this example, the word Jahresrückblick (“Wrapped” in German) is not broken in the most appropriate way (Jahresrück-blick). This was later amended for future editions.